As a child, my dream was to become a marine biologist. For a long time, I though I had missed that dream by far. Next thing I know, at 32, I am suddently meant to teach undergraduate classes in marine biology – in Spanish. Life and its twists are fun.

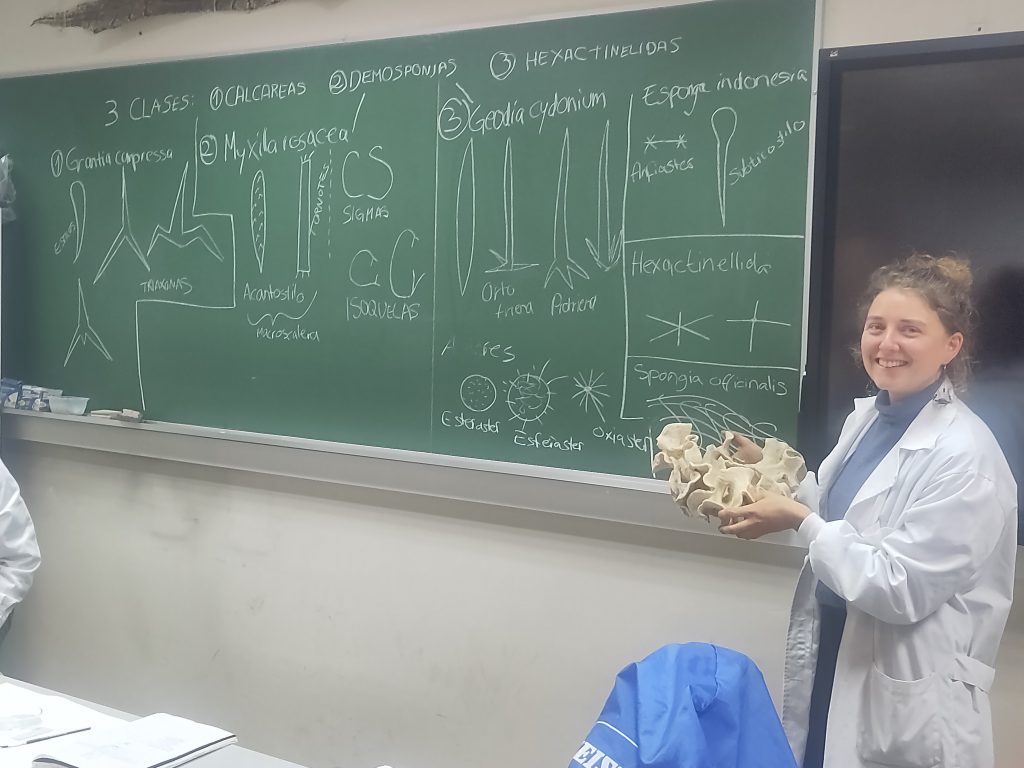

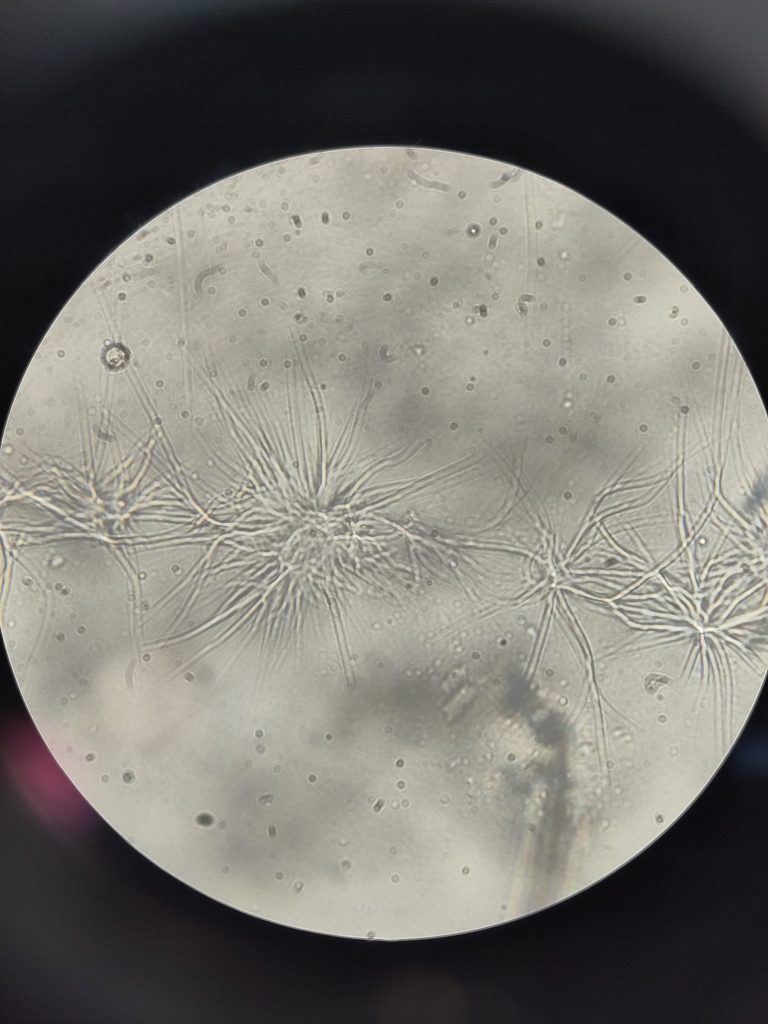

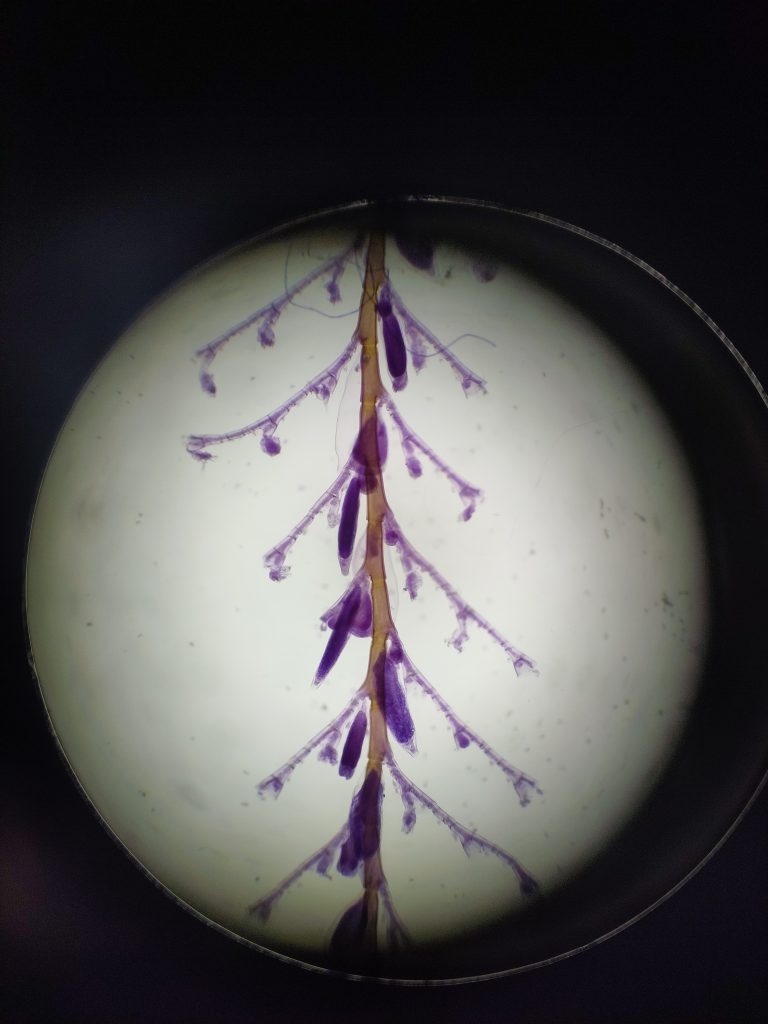

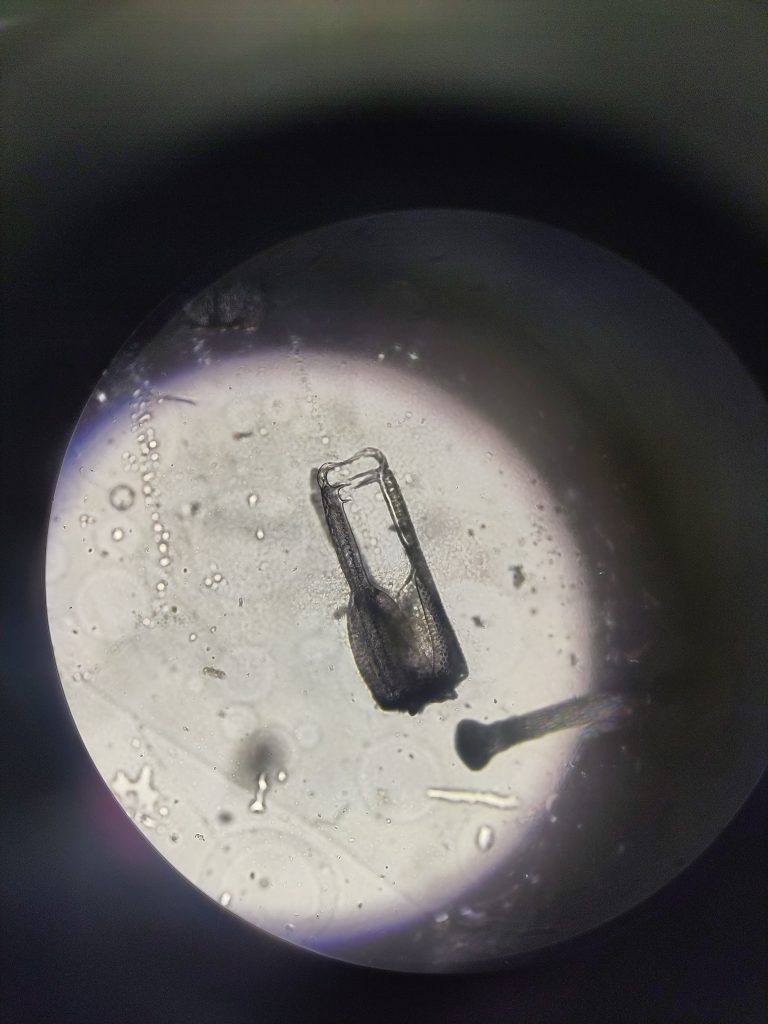

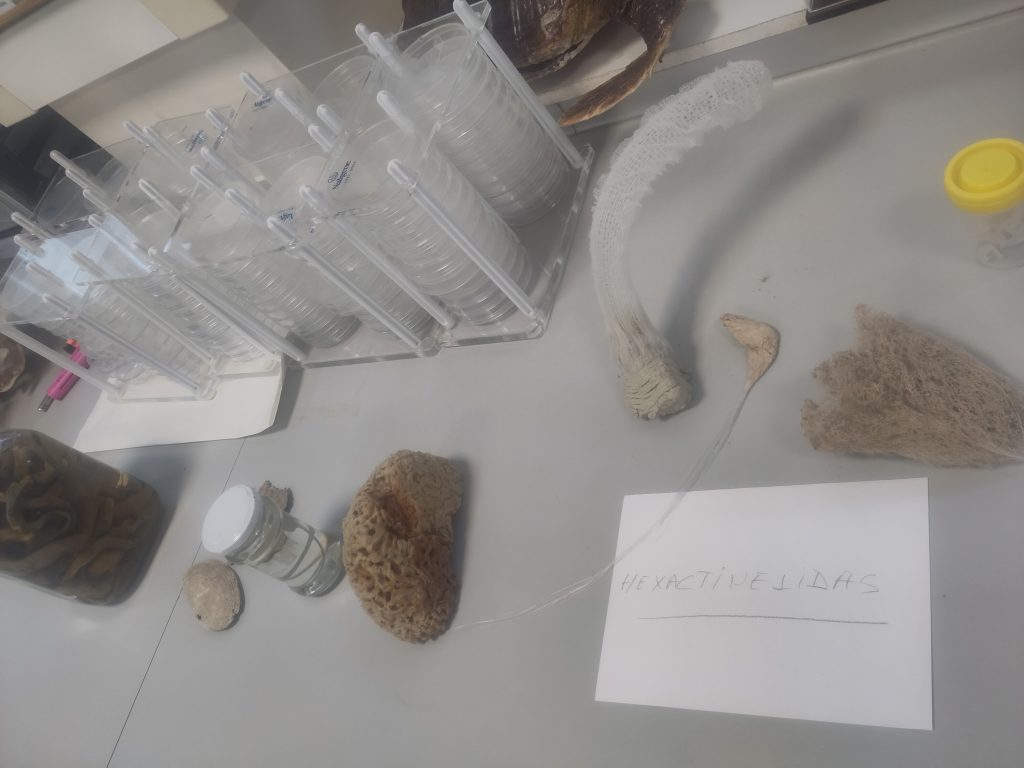

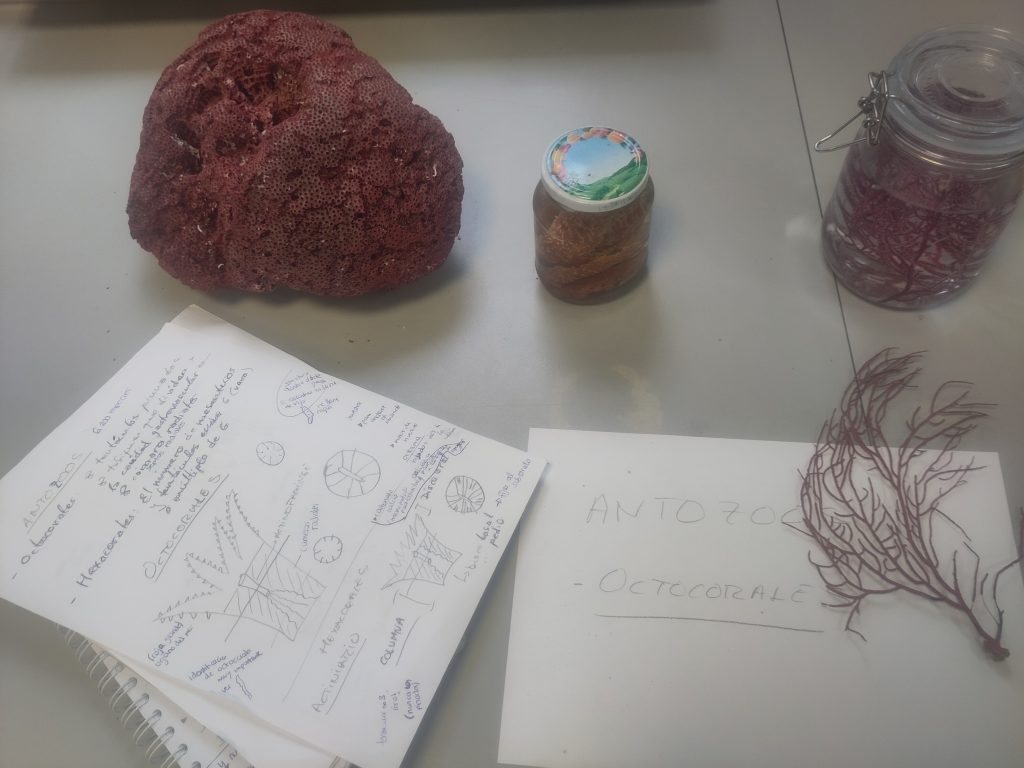

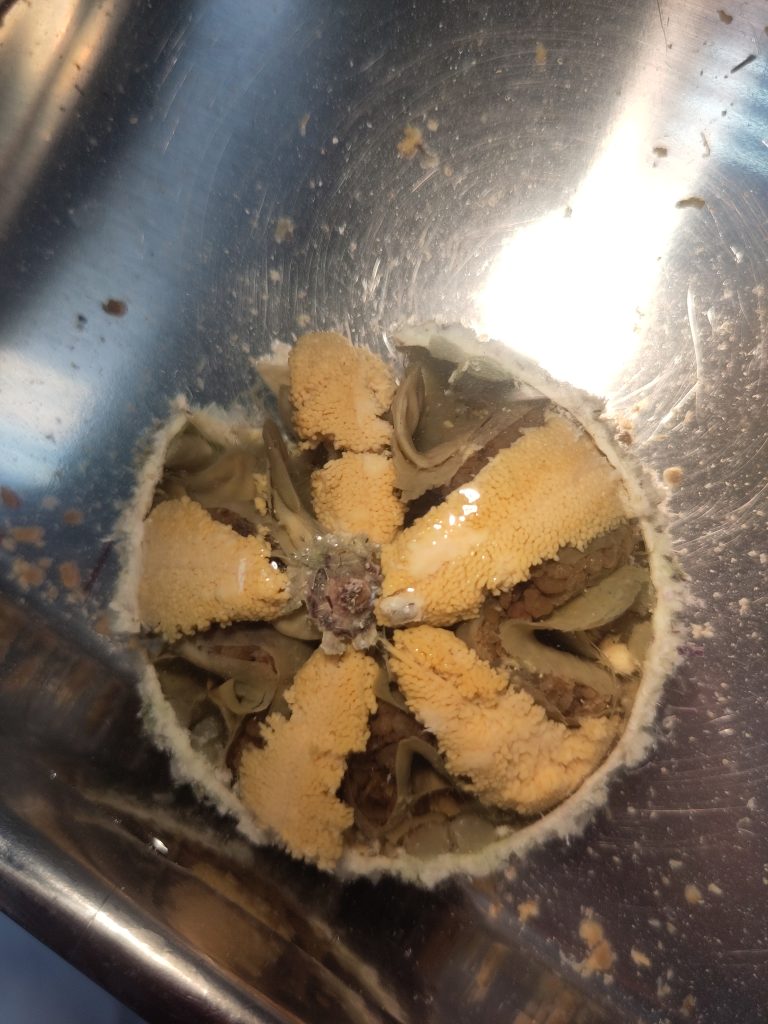

So here I am, without much experience in marine biology. Luckily, the professor was quite generous with his time, going through all the classes and practical dissections done in the course. I dissected a fish, mussel, prawn, and an urchin to prepare (the latter I might have squeezed—I clearly spend too much time climbing). I learned about sponges, how they can grow up to 2 meters and live up to 1,600 years. I discovered how diverse anemones are—and how some indigenous tribes cook a particular species for special celebrations but also use it raw to commit suicide. I learned about sea spiders, how they have four eyes and look like algae, about immortal jellyfish, and the functionally complex division of their sessile larval stage, the polyp colonies. I explored the mussel’s muscles and how they attach themselves to all sorts of substrates, the force of a crab’s pincers, the many appendages of a lobster and how they reproduce, how different groups of arthropods are so different yet still so similar, how horseshoe crabs move on the seafloor, and how the poison in some sea stars and urchins is produced.

The forms of life I got to know during those weeks were just stunning. I hadn’t heard about cephalopods before—tiny little crustaceans feeding on marine plankton.

Studying death to grasp life?

This whole dissection process raised some questions about the partitioning of biology. Sure, the students get to understand the functioning of organs, respiration, digestion, and reproduction. However, learning about different organs by actually touching them might bring them a bit closer to life—even though, paradoxically, the actual life is no longer there.

We dissect to understand, yet in doing so, we remove life from the equation. Biology, in many cases, is studied through a lens of death—preserved specimens, fixed slides, and post-mortem analysis. While these methods provide invaluable insights, they often miss the full picture. Organisms are not just their organs; they are behaviors, interactions, and adaptability in motion. This realization makes field excursions even more essential.

Since just learning “dry” marine biology is not the real thing when you live next to the coast, we went on an excursion to explore tidal ecosystems. Finally, my first ever octopus! And wow—so many more colors and forms of life to discover. Life is just so playful there. Also, from a social point of view, it was fascinating to observe what happened with the students. Some, who were normally more outspoken in the lab, became very shy and reserved, while others, usually quieter and more disengaged, suddenly turned into octopus hunters, running from one organism to the next.

The Dynamics of Teaching and Learning

Since the professors I was supporting changed, I got to observe several different teaching styles and how students reacted to them. I definitely noticed something about energy—how motivated the teachers are is mirrored in the students. The student groups also shifted. It was super fascinating to observe the different group dynamics and how differently the same tasks could be approached. Some students were definitely not made for cutting open an animal—some made such a mess, while others were naturals and so skilled.

Through all of this, I learnt how lovely it is to share knowledge with students who are genuinely interested in what you are saying. I was really lucky—the classees were just great (even accepting my pronunciation mistakes). In the end, I think I did not do too bad a job—at least in connecting with them. They even invited me to their party! Unfortunately, it was during the day and clashed with my working hours—what a pity I couldn’t go! 😀